Clothing

“There is a great demand for…better clothing, including even hoop skirts. Negro cloth, as it is called, osnaburgs, russet-colored shoes, — in short, the distinctive apparel formerly dealt out to them, as a uniform allowance, — are very generally rejected."

Edward L. Pierce, Government Agent, 1863

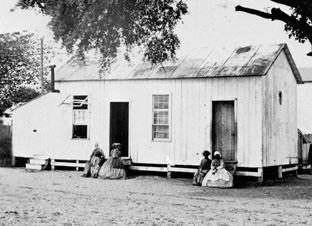

One of the most common ways people express themselves is through clothing. Enslaved people had very little say in the clothes they wore. On plantations, slaves were given clothes or fabric to make clothes several times a year. Generally, clothes were made from a cheap, coarse, durable fabric called osnaburg. Osnaburg gets its name from Osnabrück, Germany. In the mid-1700s mills in Scotland began to make osnaburg. Millions of yards of fabric were exported to England, Holland, and Great Britain's colonies. Osnaburg was used so often for clothing worn by slaves that it became known as negro cloth. When freed people at Mitchelville finally had a chance to buy clothes or material of their own choosing, they refused to buy osnaburg. The 1863 account clearly shows that Mitchelville's residents were determined to throw off their old uniforms of enslavement and create new identities as free people.

When former slaves/refugees arrived at the Union encampment at Hilton Head Island most people had few personal possessions. Often their clothes were in serious disrepair. Some historians have noted that it was likely most enslaved people who arrived at the encampment in late 1861 and early 1862 had not received their annual allotment of winter clothes. To meet the immediate need for clothing, refugees, particularly men, were often issued discarded military uniforms. Soon the missionary societies began to distribute second-hand clothes collected up north. In July 1862, The New York Times reported "some of the younger [males were] arrayed in the second-hand clothing of the officers or civilians who employ them as servants."

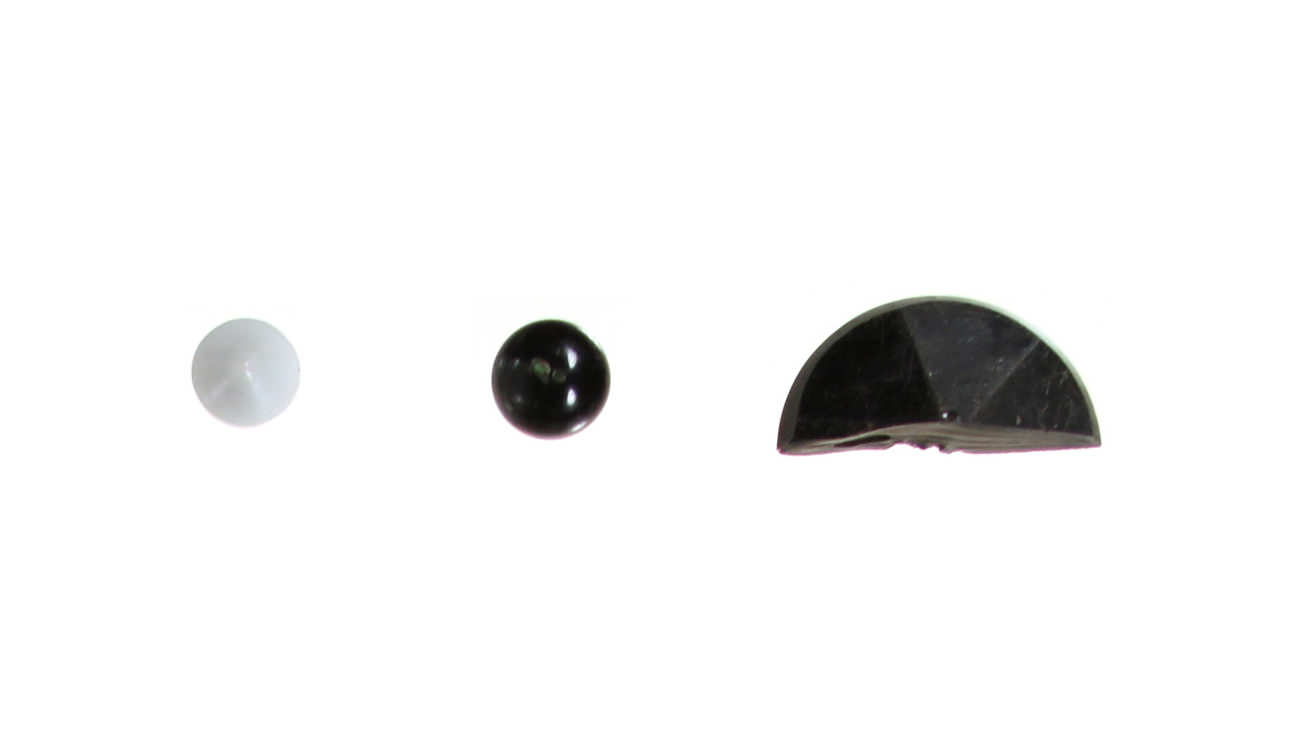

As the residents of Mitchelville began to work and earn money, they could shop at stores in Mitchelville or along Robber's Row at the military encampment. At least one of those stores, Douglas and Company, also sold military clothing. Tackaberry and Ely's store inventory included printed, gingham, flannel, and cotton cloth, silk belts, arm corsets, leather belts, thimbles, buttons, shoes laces, and collars. Archaeologists recovered 432 clothing-related artifacts including buttons, clothing fasteners, buckles, shoe parts, thimbles, and scissors that helped them learn about the kinds of clothing worn by the town's residents.

Excavation Finds

Here are some of the clothing-related artifacts archaeologists found at two houses during the 2013 excavations at 38BU2301.

| House A | |

|---|---|

| Buckles | 10 |

| Kepi buckle | 1 |

| Buttons | 33 |

| Military buttons | 4 |

| Safety pins | 1 |

| Shoe parts | 1 |

| House B | |

|---|---|

| Buckles | 35 |

| Buttons | 1 |

| Military buttons | 5 |

| Safety pins | 6 |

| Corset clasps | 4 |